As long as there is time /Dum vacat

German, Hanno Helbling, Fabio Pusterla, Massimo Raffaeli, 2002

On this page you'll find a ranking of the best Limmat products in this category. To give you a quick overview, we've already ranked the most important information about the products for you.

Fabio Pusterla, born in 1957 in Mendrisio, lives in northern Italy and teaches at a grammar school in Lugano. He has become known primarily as a poet, but also as a translator and editor of poetry from French and Portuguese and as an essayist. He was awarded the Gottfried Keller Prize in 2007 and the Swiss Literature Prize for his complete works in 2013.

As long as there is time /Dum vacat

German, Hanno Helbling, Fabio Pusterla, Massimo Raffaeli, 2002

Niklaus Meienberg, born 1940, lived in Zurich and Paris. Worked as a writer and freelance journalist, among others for the 'Spiegel', the 'Stern', the 'Weltwoche', the 'WochenZeitung' and the 'Tages-Anzeiger'. Various prizes, including the Zurich Journalism Prize, Max Frisch Prize, St. Gallen Culture Prize. The author died in 1993.

Many of these stories were written by Aline Valangin in Comologno in the Onsernone Valley, to read to her guests, including Ignazio Silone, bringing variety to the long evenings in the remote mountain village. The stories are set in a narrow Ticinese mountain valley. Aline Valangin is a keen observer of the village and its inhabitants, and her tales depict clever tricksters and rebels, drinkers and outsiders, as well as women who experienced and had to endure the hardships and challenges of life most directly. In her stories, she does not seek the idyllic, romanticized Ticino, but rather the primal, wild passions. Her characters are true, intense, and vibrant. Together, the stories form a compelling portrait of Ticino in the 1930s and 1940s, unvarnished, realistic, and virtuosic.

Even a youth revolt does not stay young forever; the revolutionaries begin to dye their hair, then stop again and turn to their advance directives. They sit by the window, looking down on a life that is no longer theirs. It unfolds in white sneakers, with bare ankles in oversized coats, jogging dresses, and knitted caps. For decades, Isolde Schaad has cast her watchful eye on acute societal events, including her own generation. With a satirical gaze, she observes the office community that revolutionizes journalism over overflowing ashtrays, only to fall into the trap of its own imagination. In cold light, the early death of the century's artist Sophie Taeuber-Arp appears as a local MeToo committee reopens the case as a criminal investigation. Whether an elderly lady at her best friend's grave pleads for the tears that do not come, or a famous author across the ocean celebrates the first day after writing, Isolde Schaad's storytelling is always refreshed with malicious humor and humanistic irony. And in between, the very latest edition of the Duden serves as a warning against the absence of gender correctness.

Switzerland is an El Dorado of multilingualism. This is also becoming increasingly evident in literature. Many authors no longer write in just one language. They fall back on a second one, which is just as closely linked to their lives, and publish bilingual poetry, novels and stories. Or they write in a national language and translate texts from their mother tongue. Or they write in their mother tongue and translate Swiss texts. These authors are constantly switching back and forth between different language worlds. Is this a gain for them? A tough challenge? The fourteen portraits ask about the motives for working literarily in two languages and what this writing in two languages means for writing and for the language(s) themselves.

Mother, where does the language stay overnight?

German, Karl Staehelin Stadler Wüst, 2014

Was it really that simple just a moment ago? Where has the order gone? But which order was it anyway? Good advice is hard to come by, and confusion reigns. 37 authors take the plunge forward, diving eagerly into disorder, into the unknown and the unnamed. They juggle with Borges' "Chinese Encyclopedia," delve into "terms that look like flies from a distance," into "masterless patterns," and into "words that belong to the author," rewriting the old encyclopedia "with a very small camel hair brush" into a palimpsest of that order which, in our eyes, is none, but which in truth simply forgoes the larger context. Those who engage with "The Handbook of Confusion" enter "collapsing spaces of possibility." For "here it wavers," just like in the rest of the world.

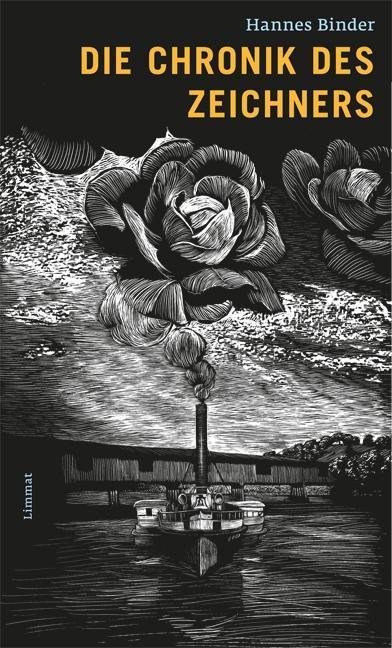

When Hannes Binder finds and reads the diaries and documents of his grandmother, he also gets to know his great-grandfather. He wanted to become a painter, but his father, a comb maker pressured by the emerging industry, urges him to think it over carefully. The successful painter Koller, whom he meets plein air, also warns him about the hard life of an artist. The documents from his grandmother's desk inspire the young artist's imagination. He travels back to the past, to the nineteenth century, when his young great-grandfather loved art and a tavern daughter from Diessenhofen, at a time when industry was encroaching on craftsmanship and the emerging photography was threatening painting. He also recalls his own youth as an art student in the sixties, embarking on new horizons. Then came the new era in the form of computers, allowing anyone to create illustrations.

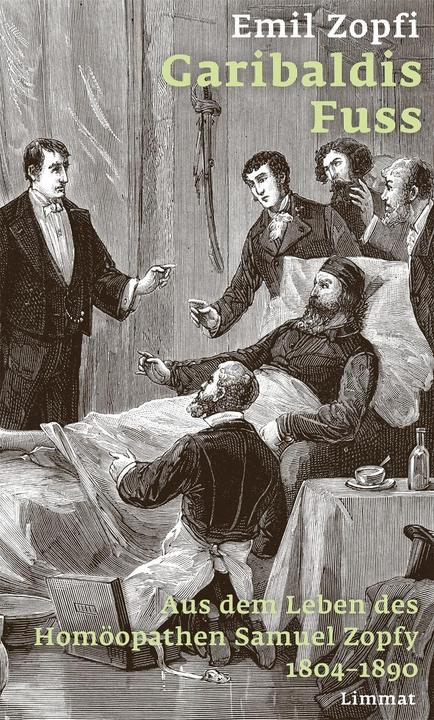

When he lived in the canton of Glarus, Emil Zopfi occasionally received a small amount of money from the Zopfi Foundation in Schwanden. A Dr. Samuel Zopfy (1804-1890) had decreed that from the hundredth year after his death, all adult "male and female members of the Zopfi family" in the canton would receive annual interest on the foundation's assets. When researching another book, Zopfi comes across an interesting story: In October 1862, Dr. Zopfy is called to La Spezia, together with the most famous doctors in Europe, to the hospital of the Italian freedom fighter Giuseppe Garibaldi to discuss his gunshot wound. How did the family doctor, surgeon, dentist and homeopath from the Glarnerland, who was also a winegrower, manufacturer and inventor, come to these honours? With the help of many sources and his imagination, Emil Zopfi tells the story e.

"Maiser" tells the story of Bruno and his family, who immigrate from the small Umbrian town of Amelia to Ticino in the first half of the 1950s. At that time, the Italian agricultural workers in Switzerland were derogatorily referred to as "Maiser." Bruno, like so many others, desires nothing more than to build a "normal" life. This is one of the central themes of our time. Until 2013, Alborghetti follows the family's journey, recounting their arrival, longing, and exclusion, the emotional struggle of being caught between two worlds, and how the initially foreign land gradually becomes home. The poetic form that Alborghetti chooses for his vivid narrative makes "Maiser" a unique and "courageous book" (Fabio Pusterla), and with the "high form" of the epic poem for "ordinary people," he compellingly harmonizes poetry with social storytelling.