Guide

Is music becoming more and more repetitive? Part 1: lyrics

by David Lee

Is there any proof to the claim that modern pop charts are just more of the same? Time to finally get some answers in part 3 of our miniseries.

Is mainstream music recycling the same formula? Too many, the answer is all too clear: of course. But after all, we need some objective proof: how else will I know my claims are substantiated and not just my own warped viewpoint?

I have dedicated a multi-part series to my search. Part 1 was about lyrics. The second part dealt with harmonic structure, i.e. chord sequences.

Both parts weren't able to properly answer the main question. There is a clear trend towards more repetition when it comes to lyrics. Only when looking at one song at a time though. We don't know whether all songs in general are becoming more samey.

Chord structures don't really help us either. Chord detection algorithms are often wrong or lacking at the very least. And examining chords by hand is very arduous. I only know one study that did that. However, it doesn't analyse historical context and looks at a relatively small sample of pieces.

Which is why I continued searching for further criteria and studies for detecting diversity in songwriting. And I found just what I'm looking for.

Detecting tone is another important element in measuring the variability of a song. It's largely determined by the instruments used. Think of the typical 80s sound, established through a rather excessive use of synthesizers. Bass and drum duties were often also taken over by synths, with a whole lot of fake reverb to boot.

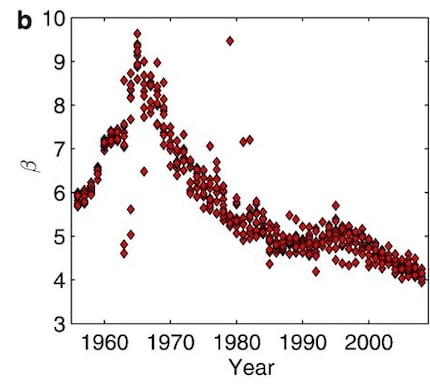

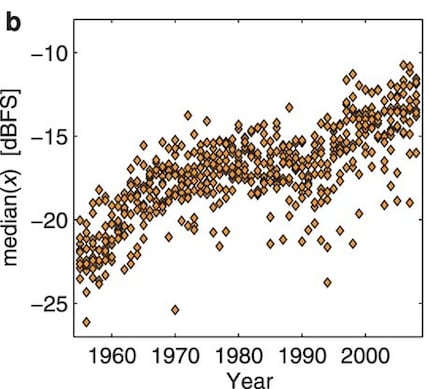

A study examined the timbre, i.e. tone. The researchers relied on the Million Song Dataset – a collection of data with information on one million songs, freely available for download. About half of these songs are undated and therefore useless for our investigation. After deducting duplicates, incomplete entries, and entries from before 1955, there are still 464,411 recordings from between 1955 and 2010.

A clear result: between 1955 and 1965 there was an increase in the variety of tone, followed by a continuous decline.

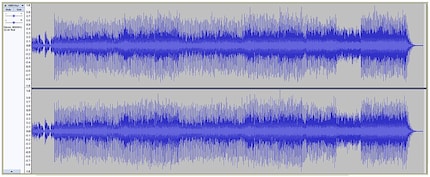

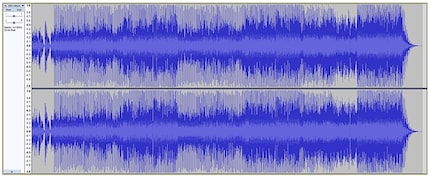

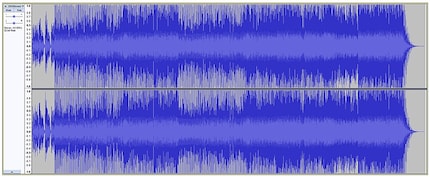

The same study is also devoted to the infamous development of loudness. You've surely noticed that recordings from different albums can vary widely in volume. While the loudest sounds tend to be the same, the «rest» still seems to differ by song. Audio compression can be used to reduce peak volumes while increasing quieter ones. This allows the overall volume to be massively increased without overloading the peaks.

And that's what they've been doing for decades. This is comparatively easy to measure, with much evidence to prove a trend.

What does this have to do with diversity? Well, if every piece of music is consistently loud, it inevitably makes the musical landscape more monotonous. No dynamics, no alternation between loud and quiet. Nevertheless, producers always push volume to the limit and sometimes even beyond. After all, louder songs attract more listeners. Pieces with very complex dynamic structures are also impractical as background music or in noisy environments such as cars. Quiet parts are hardly audible. Unless you turn your stereo up to earbleedingly loud levels.

Finally, the study also deals with «pitch». Combining all pitches played at any specific moment gives us insight into chords. Pitch therefore refers both to melodies and to the underlying harmonies.

Researchers have found that there is a trend towards fewer, more frequent transitions than in the past. Clearly: there is a tendency towards playing the same melodies and harmonies.

An example of a tone sequence that I'm sure you're sick of hearing is the «Millennial Whoop». It's a super simple melody consisting of only two notes – the third and fifth notes of a major scale. The passage is characteristically sung without text – think «oh-ah» or similar. It's the same tone sequence as when «Olé olé» is sung in a football stadium, except that the Millennial Whoop usually begins with the higher tone.

Katy Perry clearly performs the «Millennial Whoop» at 1:05 in this video.

The term Millennial Whoop was coined by Patrick Metzger in his highly acclaimed blog entry. With the help of his readers, he has compiled an impressive list of examples.

Here's a song only consisting of mashed-together Millennial Whoops.

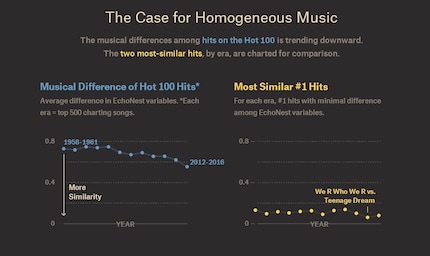

There's another study that automatically compared a large number of chart songs. And its methods sound promising: researchers got Spotify to suggest similar songs to users.

The start-up «The Echo Nest» has developed a method that automatically analyses songs according to eight criteria that describe how a song sounds. Echo Nest was acquired by Spotify in 2014. The criteria are:

With all eight criteria combined, you can determine how similar two songs are. Since EchoNest doesn't keep this data to itself, Andrew Thompson and Matt Daniels were able to examine the top 100 US chart singles from 1958 to 2016. The result: until 1981 the diversity of the 500 most successful songs remains roughly the same, then it decreases for 10 years. Between 1992 and 1996 diversity increased again, but since then it has continued to decline. Most recently falling between 2012 and 2016.

But that doesn't mean that everything sounds the same these days while everything sounded different back in the good old days. Every period contains extremely similar number 1 hits and key differences. At least according to the EchoNest calculation.

The two most similar number 1 hits come from the oldest period, 1958-1961:

These two number 1 hits from 2007 and 2011 sound very different:

The studies presented here give us a clear picture: chart music is becoming more and more uniform. That doesn't mean that music is getting more monotonous, only mainstream singles are.

The next part in this series should be the most exciting because it's about the reasons why.

Follow my author profile to be alerted when it comes out. Here's another link to the Spotify playlist with all songs used in this series.

Cover picture: 10,000 Hours by Dan + Shay/Justin Bieber

My interest in IT and writing landed me in tech journalism early on (2000). I want to know how we can use technology without being used. Outside of the office, I’m a keen musician who makes up for lacking talent with excessive enthusiasm.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all