Background information

Visit the exhibition of portrait photographs taken by our Community members

by Carolin Teufelberger

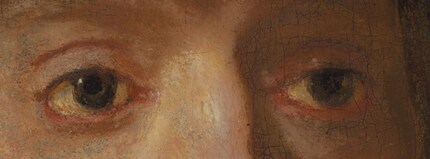

At first glance, the digital painting with its gigantic resolution doesn’t look particularly spectacular. For research on the other hand, the microscopic details are proving useful.

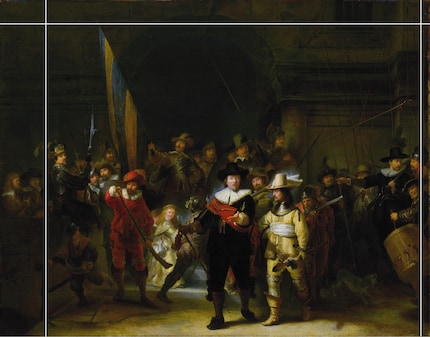

The Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands has digitised a painting using a staggering resolution of 717 gigapixels (717,000 megapixels). According to the museum, the image is made up of 8,439 individual photos, each 100 megapixels. These were photographed with a Hasselblad H6D 400C, then pieced together into a complete image with the help of artificial intelligence.

The painting in question here is «The Night Watch» by the Dutch painter Rembrandt. Dating back to 1642, it measures in at 363×437 cm.

You can have a look at the result in your web browser. Zooming in is less spectacular than the panorama in the gigapixel section, which allows you to suddenly discover new houses or hills. In contrast, the high-level zoom doesn’t have much to offer in the way of new revelations.

The ultra-high resolution wasn’t initially created with your typical gallery visitor in mind. In fact, it’s needed first and foremost for image research and restoration.

The museum notes that they’re able to quickly identify pigments of similar colours with the help of neural networks. With the same technology, it’s also possible to distinguish lead soap, a substance which speeds up the deterioration of paintings.

The gigapixel photo is one of a few projects that have been running since 2019 under the name «Operation Nightwatch». Each project aims to research «The Nightwatch» while keeping it as close to the original as possible, which, in this case, is particularly ambitious.

In the past, nobody was that bothered about preserving paintings. Up until 1715, Rembrandt's «The Nightwatch» was more than five metres wide – considerably bigger than it is today. Back then it was hung in Amsterdam City Hall in a room between two doors – a spot that it didn’t remotely fit into, which led to a couple of strips being unceremoniously lopped off the ends.

The consequence? The painting’s two main figures are located in the middle of the picture instead of slightly to the right, and no longer appear to be strolling into the frame. Rembrandt’s meticulous composition was destroyed by the knife wielder’s handiwork.

Not only that, but two musketeers and a small child were completely cut out of the left-hand side of the painting. At least two of the adults portrayed were real people, but because they’d already died by 1715, they couldn’t exactly protest their removal. The same goes for Rembrandt.

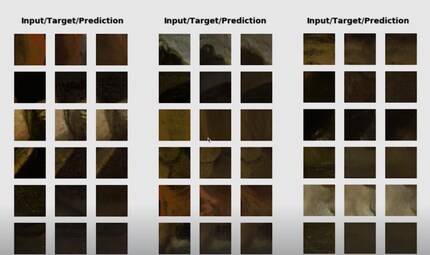

The cut-away parts of the picture were never to be found again. It’s only thanks to a very old copy of the painting that we even know what the original must have looked like.

The painter of the copy couldn’t imitate Rembrandt perfectly – both paintings differ in proportion and style. In spite of this, specialists have used machine learning to piece the missing scraps and the original back together. The first step is to bring any discrepancies in line with the original so that both pictures can be superimposed exactly. After that, another neural network is programmed to recognise Rembrandt’s painting style. To do this, the researchers break the picture up into small tiles. The AI then has to generate a copy for each one, as close to the original as possible. The process is repeated until the system’s performance is up to scratch.

In this museum video, you’ll see that the result isn’t perfect. Maybe the restoration will be better with the new 717-gigapixel picture.

My interest in IT and writing landed me in tech journalism early on (2000). I want to know how we can use technology without being used. Outside of the office, I’m a keen musician who makes up for lacking talent with excessive enthusiasm.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all

Background information

by Carolin Teufelberger

Background information

by Samuel Buchmann

Background information

by Thomas Kunz