Background information

Meta under pressure – Part 3: TikTok, the Chinese juggernaut

by Samuel Buchmann

Negative headlines surrounding Meta and its Facebook and Instagram brands are piling up. Is Mark Zuckerberg facing his downfall? Part one of a series on the tech giant’s problems.

Would extra days off introduced during the pandemic continue in 2023? The pre-recorded question posed by poor, clueless Gary from Chicago at a virtual Meta meeting came at the worst possible time. Just before that, Mark Zuckerberg, Meta’s untouchable ruler, had gone on a tirade: Employees should really start working harder again and be available for meetings on normal work days. And besides, «Realistically, there are probably a bunch of people at the company who shouldn’t be here.» That sunk in. The mood had hit rock bottom. And Gary’s days off? Cancelled.

Realistically, there are probably a bunch of people at the company who shouldn’t be here.

The episode is symptomatic of a trend reversal at Meta. Its glory years are over, its future uncertain. Zuckerberg’s empire is under pressure from all sides: Facebook has become uncool. Instagram is drawing massive criticism from its star influencers for alienating its roots. Tiktok is draining advertising dollars from both platforms, and Meta is desperately trying to jump on the short video bandwagon. Speaking of advertising money: Apple seems to have declared war on Meta – and you really don’t want the world’s most valuable tech company as your enemy. And the Metaverse, Zuckerberg’s futuristic saviour? Doesn’t seem to be convincing anyone yet.

What happened, and what’s next? To answer that, I’ll embark on a journey into Meta’s past, present and future in this series. In the first part: how Facebook became uncool.

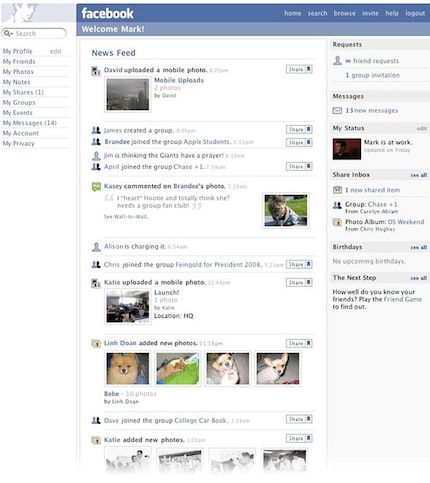

Do you remember the early days of Facebook? For me, the golden years of the platform happened while I was at uni. Back in 2010, Facebook was the place to go to network with other people. Practically all my friends used it. The newsfeed was full of familiar faces. We used the platform for everything, from memes through organising parties to page-long discussions on exam material. Facebook was what it promised to be: A The Social Network.

Millennials such as myself and anyone younger have long since abandoned the platform. Facebook has become Boomerville.

There’s precious little of that left. When I log on to Facebook today, I see mostly ads, posts from professional sites – and content that I don’t even know why I’m seeing. Every now and then, a photo by one of the last Mohicans who still posts photos on Facebook at will appear. They’re usually at least one generation older. Millennials such as myself and anyone younger have long since abandoned the platform. According to recent surveys, the percentage of teens using Facebook has dropped from 71 per cent to 32 per cent since 2014. Facebook has become Boomerville.

To understand how this could happen, you need to understand how Facebook’s algorithms have changed over the years – after all, they decide what you see. They were born in 2006, together with the News Feed. The idea of scrolling through such a feed seems self-evident today. At the time, it was revolutionary: you no longer had to actively visit your friends’ profiles to see what they were up to. Instead, all the news was handed to you, bundled together on a silver platter.

This original algorithm was very simple: you only saw posts from people and sites you were subscribed to. What was newest ended up on top. That changed in 2009 with the introduction of the Like button. Facebook started sorting posts not only by recency, but also by popularity. In a nutshell: posts with more clicks and more likes were pushed to the top. This led to an explosion of clickbait, and Facebook was forced to continually adjust its algorithms.

By 2016, they had finally changed so that the value of a post was measured primarily by how much time users spent with it. In addition, videos were pushed as a new format. The result: a flood of professionally produced paragraphs, images and videos that tried to hold your attention for as long as possible.

There was a growing fear of losing users to other platforms such as Snapchat, where interactions were more social and personal. And so, Facebook once again sought its salvation by changing its algorithms. The next idea: maximising time spent was no longer at the forefront, but «Meaningful Interactions». Facebook started giving preference to posts from friends over professionals again. However, there was a twist: the more comments a post attracted, the more it was shown.

If you were ever on Facebook during the Covid era, you probably know what effect this new algorithm had. The platform was full of controversial posts, disinformation and conspiracy theories. Makes sense, as topics like these provoke fierce exchanges in comment sections. This was recognised by professionals, who set up entire troll farms to influence political discourse.

Whistleblower Frances Haugen revealed that Facebook was aware of the damage it was doing.

The extent to which the new algorithm contributed to disinformation, and that Facebook was aware of this too, became known at the end of 2021. Whistleblower Frances Haugen leaked documents from internal investigations. According to the leak, Facebook itself estimated that by eliminating «Optimisation for Engagement», it could reduce political disinformation by up to 50 per cent. In a statement, the company claimed the leaked documents had been taken out of context. But the fact that the new algorithm rewarded polarising posts and thus provided a huge platform for borderline content cannot be denied.

The algorithm’s unwanted side effects provoked widespread criticism. And they were far from the only thing doing damage to Facebook’s image. In addition, there were more and more data protection concerns. The company evolved into an octopus, collecting as much data as possible and using it to create profiles. It ultimately sold these to advertisers, who could then place their ads in a more targeted manner.

They trust me. Dumb fucks.

Mark Zuckerberg doesn’t consider the fact that many users don’t know or understand data protection to be Facebook’s problem. His attitude towards privacy is shown in an IM excerpt with a friend during the early days of Facebook, to which only Harvard students had access at the time:

Zuck: «Yeah so if you ever need info about anyone at Harvard»

Zuck: «Just ask. I have over 4,000 emails, pictures, addresses, SNS.»

**[Censored friend’s name]: «What? How’d you manage that one?»

Zuck**: «People just submitted it.»

Zuck: «I don’t know why.»

Zuck: «They "trust me".»

Zuck: «Dumb fucks.»

Zuckerberg didn’t put it quite so drastically in subsequent years. But to this day, he continues to push responsibility regarding data protection away from himself. In 2010, he said on the subject, «What people want isn’t complete privacy. (…) It’s that they want control over what they share and what they don’t.»

What people want isn’t complete privacy. (…) they want control (…).

Public distrust of Facebook reached a peak in 2018. The «New York Times» and «Guardian» revealed that a company called Cambridge Analytica had collected and misused data from Facebook users on a large scale. It used this

to influence the 2016 U.S. elections through targeted advertising. To do this, the company took advantage of Facebook’s lax privacy policies: it had a third-party company develop a Facebook app called «This is your Digital Life» in which users took a personality test. 270,000 people did so, sharing their own data with the app as well as the data of their friends – without their consent.

The act alone wasn’t illegal, but Facebook giving its app developers this much room to manoeuvre was. Zuckerberg once again tried to shift responsibility, saying that, according to Facebook’s regulations, all this data should’ve been used only to «improve user experience on the app.» But that didn’t distract from the fact that a lack of data protection had opened the door to abuse. Finally, Zuckerberg apologised publicly – but the damage to his image had long since been done. In the wake of the scandal, the Facebook CEO even had to appear before the U.S. Congress and face uncomfortable questions regarding data protection and Facebook’s quasi-monopolistic position. This video contains some highlights of the hearing:

All these missteps regarding algorithms, disinformation and privacy made Facebook what it is today: a juggernaut that I personally hardly use anymore – and my younger colleagues even less so. The quality of the content is simply too poor and the privacy concerns are too great. So far, this hardly seems to have made a financial dent. The lion’s share of Meta’s advertising revenue still comes from Facebook. The company owes this to two groups in particular: older users and those from emerging markets such as India.

But such individuals aren’t trendsetters. Dark clouds are brewing over Facebook – take statistics on the top ten apps in the App Store. While Facebook fell short of the top ten for only seven days in 2021, that number rose to 97 days in 2022. Young people especially are less likely to install the app on their first ever smartphone. And they’re the future.

Mark Zuckerberg’s answer to the crisis? The same as always: new algorithms to the rescue – «Discovery Engine» is the name of his latest attempt. More on this in the episode after next. In part two of my series, I’ll first get to the bottom of one of the tech industry’s most successful acquisitions, the story of which simultaneously reveals Meta’s problematic strategy: Instagram.

Cover image: an art installation outside the U.S. Capitol on the day of Mark Zuckerberg’s hearing. Image: Michael Reynolds/Keystone

My fingerprint often changes so drastically that my MacBook doesn't recognise it anymore. The reason? If I'm not clinging to a monitor or camera, I'm probably clinging to a rockface by the tips of my fingers.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all