Background information

Unplug the power supply: the story of Konrad Zuse

by Kevin Hofer

Computers from the Soviet Union? Weren’t they all just IBM ripoffs? Nope. Join me as we discover how Soviet computer pioneer Sergey Lebedev devised the Soviet Union’s first digital computer in the early 1950s, under adverse circumstances no less.

Kiev, 1949. More precisely: Feofaniya. A monastery which had been severely battered during World War II, in a suburb near the Ukrainian capital. Workers perpetually flow in and out to repair the building. This is exactly where Sergey Lebedev and his team planned to develop the Soviet Union’s first digital computer.

However, the local infrastructure was anything but satisfactory. The monastery had no central heating. His team has to chop wood to fire the few fireplaces. Even worse, the journey: Feofaniya is located 15 kilometres outside Kiev. There wasn’t public transportation or paved roads at this time. Therefore, the team members had to be driven there by an old Soviet truck – a Guzik. It often got stuck in mud during spring and autumn and in snow during winter. To even get to their workplace, they had to resort to some good old pushing. Which is probably why some team members decided to live in the monastery.

Making it all the more amazing that, under these circumstances, Lebedev and his team managed to build a computer and get it running in November 1950.

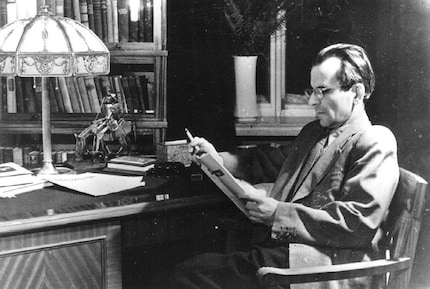

Sergey Alexeyevich Lebedev was born on November 2, 1902, in Nizhny Novgorod in present-day Russia. His parents were teachers. They did everything they could to quench their young boy’s thirst for knowledge. Even as a child, he was interested in electricity and had built a dynamo himself. He also played the piano and recited poetry.

Shortly after the 1917 October Revolution, Sergey’s father and family were sent to the city of Sarapul. Only to be transferred to Moscow a year later. Sergey and his father left for the capital of Russia by themselves. Shortly thereafter, his mother fell quite ill, meaning Sergey had to take his sister and mother from Sarapul to Moscow alone. An arduous journey that would shape Lebedev’s confident, independent personality.

In 1921, he began studying electrical engineering at the Moscow Technical University. Here he specialised in high-voltage technologies. After graduation, he taught and helped design power plants and transmission technologies. Even early in his career, he already held senior positions. He was considered very helpful and modest. Receiving no appreciation for achievements he helped inspire didn’t bother him much. He wasn’t much attracted to prizes or praise. Lebedev was energetic and calm at the same time. An avid mountain climber, he scaled the 5642-meter Elbrus at 35, the highest peak in the Caucasus.

During this time, Lebedev had to solve linear and non-linear differential equations. Due to their difficulty, he started dreaming up mechanical methods of calculation. He was inspired, among other things, by mechanical analogue computers such as those developed by Vannevar Bush. In the 1930s and 1940s, Soviet research moved toward analogue devices.

In 1943, Lebedev went to Moscow and became head of the new Department of Automation of Electrical Systems at the Electrical Engineering Institute. Following this in 1946, he was appointed director of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. Here he became increasingly concerned with the problem of automatic calculation.

Initially, he focused on analogue devices, before turning to digital computers relatively quickly. Together with like-minded mathematicians, electrical engineers and physicists, he developed concepts and principles that flowed into the Soviet Union’s first digital computer: MESM (Malaia Elektronnaia Schetnaia Mashina – Small Electronic Calculator)

.

But before that could happen, Lebedev had to convince the Academy of Sciences to set up a special, secret laboratory to conduct research on electronic computers. He thankfully succeeded. In 1948, he began recruiting personnel for his laboratory. Most of the up to ten employees had never heard of electronic calculating machines before. Initially, a lot of time had to be invested in training. But by the end of 1948, the team was ready, and Lebedev had prepared basic designs for the machine.

In 1949, the laboratory grew to 20 employees. Preliminary construction work had been completed. Now, however, Lebedev was facing a problem: where in war-torn Kiev would he build this machine?

Kiev had suffered greatly during the war. Above all, there was a lack of accommodation and building space. In addition, few people in the 1940s realised the potential of digital computers. Fortunately, the Ukrainian Academy of Science agreed to make the monastery in Feofaniia available.

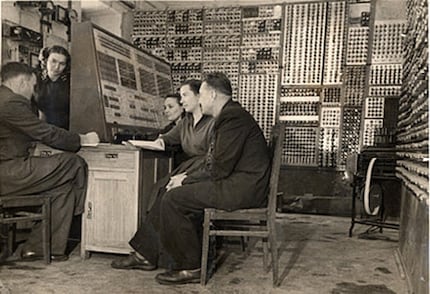

In addition to the heat, distance and shoddy roads, Lebedev had to overcome another challenge. The monastery was large, but none of the rooms were big enough for his «small» electronic calculator. It took up a good 50 square metres of space – about 1.3 times the size of a boxing ring. Therefore, rooms in the monastery had to be enlarged.

Boris Malinovsky, expert on Soviet-era computers, talking about MESM and Lebedev.

When construction finally began, more problems quickly arose. For example, loose cables gave off voltage to the housing of the machine. If employees weren’t careful, they’d be hit with a 250-volt shock. Which made developing special insulation extremely necessary.

Another problem was the approximately 6000 vacuum tubes on MESM. Due to the tricky manufacturing process, each tube was unique. However, since they ran parallel to each other, at least two tubes would always have to have the same properties. Therefore, Lebedev’s team had to test all the tubes and divide them into pairs accordingly. To find a suitable pair, they may have had to test thousands of tubes.

But that wasn’t the only problem with the tubes: in the course of their life cycle, their properties change. In addition, as soon as the machine was switched on, the tubes oscillated for about two hours. During this time, the whole setup unusable. Which is why MESM was simply left running – aside from servicing, of course. One final problem with the tubes: they generated a lot of heat. In winter, the room got to a good 30 degrees Celsius, even 40 during summer. Since there was no air conditioning, the tubes had to be cooled with hand-operated fans. Nevertheless, tubes would still sometimes give off random signals due to the heat, requiring the machine to be shut down as a result.

To solve these problems, Lebedev expected his employees to work even in the evening sometimes. Often, he himself wouldn’t finish work until 3 o’clock in the morning.

Despite the hard work, Lebedev and his employees enjoyed their lives at this time. They discussed problems during walks in the nearby forest or at the lake. It’s even said that he himself had a favourite tree stump on which he’d often sit and think. While doing so, he’d take notes. Not always in his notebook, however, but on his cigarette pack. Lebedev smoked a lot.

But on November 6, 1950, the time had come: MESM solved its first, simple calculation: what’s 2 × 2? Fortunately, the machine almost always gave «4» as an answer. By 1951, MESM was fully operational. Starting in 1952, it even performed top secret calculations for missiles and nuclear weapons. MESM ran until 1957 before being taken out of service. Today, it’s considered the first functioning electronic calculating machine invented on the European mainland.

MESM is an even greater achievement when you consider that only about 20 people were involved in its development. It’s U.S. equivalent ENIAC was larger and more powerful, but it also had over 200 people working on it.

Lebedev was already busy with other projects at this time. BESM-2 – Fast Working Electron Calculating Machine 2 – was Lebedev’s first mass-produced computer in 1958.

Lebedev wasn’t the only one working on electronic computers in the Soviet Union at this time. Largely isolated from each other, teams across the country developed computing machines. The Soviet computer sector was therefore highly fragmented until the 1960s. A combination of machines from different series was missing, neither did they use a uniform bit length, which complicated transmission. A big reason why production figures remained small when compared to computers manufactured in the USA.

The Soviet Union also lagged behind the U.S. in terms of software. In the USA, computer programs ensured that devices could also be operated by non-professionals. In the USSR, programming remained exclusive to manufacturers until the late 1960s.

Around this time, however, there was a consensus among Soviet computer experts that a separate line of compatible computers was needed. In other words, computers that were compatible with each other and communicated using a uniform language. Lebedev disagreed. He doubted the technical feasibility and usefulness of such a computer series.

Nevertheless, proponents of compatible computers were gaining ground. With the help of East German espionage activities, they succeeded in copying IBM’s System/360. Yet despite these copies, the Soviet Union didn’t succeed in catching up technologically with the West, led by the USA, until its collapse.

Lebedev insisted on developing structures for parallel computation and intensifying research on parallelism in calculations. He also predicted that high-performance supercomputers would become important in the future. His own series of such machines was ELBRUS, named after the highest peak in Europe, which he had climbed at 35.

However, he never got to see his supercomputers. He died in Moscow on July 3, 1974, aged 71, after a long illness. In total, he and his teams had developed over 18 mainframes in just over 20 years. In 1996, he was posthumously awarded the Computer Pioneer Award. An award he himself would probably not have cared about.

From big data to big brother, Cyborgs to Sci-Fi. All aspects of technology and society fascinate me.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all