Background information

Why the world’s largest e-car never needs to charge

by Dayan Pfammatter

Apple has been quite quiet about culling its wireless charging station, AirPower. But I think the company made the right decision – and I’m going to tell you why.

My colleague Kevin Hofer recently checked if you could save more money by using a monitor with an A++ energy efficiency rating rather than a A-rated one. This was Kevin’s verdict: «You can’t really save any money with an A++.»

I need to give Kevin a hard stare at this juncture, as I don’t agree with him at all. It stands to reason that it’s hard to save money on electricity because the latter is so cheap. If people had to generate their electricity from an exercise bike, 100 watts would seem real all of a sudden. And of course, that would mean a huge step backwards in terms of convenience.

And that’s where I draw a parallel with wireless charging: the convenience factor. There’s no fiddling around with the cable. You just pop your device on the pad and it already starts charging. Given there are no more charging sockets with exposed contacts, you can get products with better waterproofing.

There are already a few wireless charging solutions and many smartphones are designed with wireless charging options. In terms of Android, induction smartphone charging has been around for some time now. Even Apple phones have had wireless charging enabled via Qi (standard) since the release of the iPhone 8.

The thing with induction is that electricity transmission from the charging mat to the smartphone is inefficient. The Swiss Federal Office of Energy (SFOE) had the technology investigated and the findings showed a snag with this kind of charging. According to their reports, if all smartphones in Switzerland switched to induction charging mats, it would require 30 GWh more energy than if the devices were charged with a traditional cable.

Although, that admittedly only amounts to «slightly more per mille for an average Swiss household’s yearly electricity usage», as outlined in the report from the Swiss Federal Department of the Environment, Transport, Energy, Communications DETC(in German). Abstract in English available here. That being said, this extra amount would cover the average usage of more than 6,000 four-person households.

What the authors of the report find particularly problematic is the fact that, comparatively speaking, charging pads use a lot of energy when they’re on standby. When there is no device on the mat, it behaves similar to a conventional power supply. However, once the mat detects a device, it tries to charge it. Once the device’s battery is fully charged, the mat’s energy consumption does drop but not to the standby value permitted by law, which is 0.3 W. According to the report’s authors, the worst case scenario is that more energy is being lost than the total needed to charge the device.

Transfer of energy via induction has been around longer than smartphones. Take electric toothbrushes, for example. They’ve long since relied on induction in a room in the house where damp is an issue. And in the kitchen, induction hobs are old hat. After a spot of research, I quickly discover that induction hobs are superior to glass-ceramic and gas stoves.

I’m confused. Is induction technology good or not? I decide to put my question to the authors of the DETC report directly and hop on a call with Marco Zahner from Fields at Work, a «spin-off» company supported by the technical and scientific Zurich university ETH.

«Induction isn’t bad or inefficient per se,» explains Marco. «For instance, transformers only work because of induction. Systems that relied on induction from the start are usually efficient,» he continues. Marco adds that inefficient systems tend to be those that had induction added afterwards, such as the smartphone example. According to Marco, the problem isn’t the charging mat. Most of the energy is in fact lost on the receiver side.

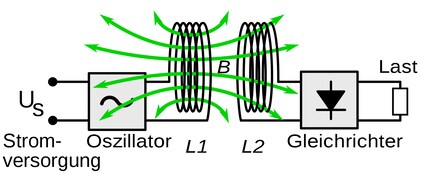

Operating principle of energy transfer using induction Image: Wikipedia)

Back to Apple’s wireless charging station, AirPower. It must have been a last-minute decision, as the charging pad was even depicted on the packaging for the new AirPods charging case. That surely can’t have been easy for the iPhone maker.

Why Apple decided to bury its wireless charging solution isn’t known. But what we do know is that the Californian company wanted to unveil a charging pad that featured a number of coils, which would enable users to charge several iPhones, AirPod cases or Apple Watches at once. It’s also conceivable that Apple wanted to use all these extra coils to create something that would do away with the need to position devices in an exact way on the charging mat. This would have represented a real advantage over traditional solutions.

But that’s enough of my analysis. What do the experts think caused Apple to fall at this hurdle? Marco from Fields at Work is reluctant to call it. «Most companies use the Qi reference design,» he reveals. Marco goes on to explain that it’s unlikely manufacturers will take the time and effort to change solutions or improve it with more expensive materials.

That’s where Apple was bolder than other manufacturers. «If you want to build a charging pad using a number of coils, that’s when you’re going to rapidly exceed the permitted limits for electromagnetic fields because the fields overlap,» explains electrical engineer Marco. He reckons that solutions based on several coils are generally more problematic. «It’s exponentially more difficult to build a system with a number of coils,» he clarifies. As energy «lost» in the induction process is transformed into heat, you also have to consider smartphone overheating issues.

Marco rounds up our conversation by dropping another bombshell: there are also problems with USB charging cables. «Poor USB cables have up to 1 ohm internal resistance,» he says. «The influence of this inconspicuous component is often underestimated.» Ah, that’s why it can take much longer to charge up with some cables than others. In which case, it looks like I’ve already got material for my next article. If you follow my profile, you’ll get a notification once it’s published ;).

I'm the master tamer at the flea circus that is the editorial team, a nine-to-five writer and 24/7 dad. Technology, computers and hi-fi make me tick. On top of that, I’m a rain-or-shine cyclist and generally in a good mood.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all