Background information

Mainstream monotony in music, part 4: cold hard truths

by David Lee

Endless AI-generated songs are flooding streaming portals – a relatively new problem. But all it does is reinforce older, familiar problems.

AI songs are quickly generated and don’t require any specialised musical skills. No wonder, today’s world is flooded with computer-generated songs. In just a year, Spotify has removed no less than 75 million tracks from its catalogue. The reason? It was all AI spam. Competitor Deezer, which has been taking action against AI songs for longer than Spotify, deletes 30,000 tracks every day – trending sharply upwards. Extrapolated over a year, that’s 11 million pieces of music.

And AI spam doesn’t just clog up portals: it’s also a basis for fraud. Bots listen to AI-generated songs automatically, and their creators collect licence fees. Spotify and its ilk are trying to counteract this with the automatic detection of bot behaviour.

But as the Guardian reports, real artists get blocked this way too. The algorithms aren’t reliable. Even just one song being streamed too much is often enough for a block. However, this might happen organically too, for example if a song is played on radio or goes viral on Tiktok. This makes it difficult for artists to contact the streaming provider. It’s even harder to prove you’re innocent.

AI poses a very fundamental problem for musicians too. Their work could become largely worthless in the future. Why use musicians when you can just create new music at the touch of a button?

Here’s my view: these problems aren’t that new – they’re just being aggressively amplified by the AI flood. Let’s take a closer look.

Even before this invasion of AI slop, humans were creating way more content than anyone would ever want or listen to. Or as Forbes describes it: demand for music always stays about the same, while supply grows exponentially. Even without AI, it’s becoming easier and easier to make music that sounds good enough. In the last century, a band had to rent a professional recording studio and hire specialists who knew what to do there. Today, an ordinary laptop or even an iPad with an audio interface is enough. Good software doesn’t cost a fortune, and does more than even the priciest equipment was able to. In addition, anyone can publish their works on platforms such as Spotify. This wasn’t possible in the past either.

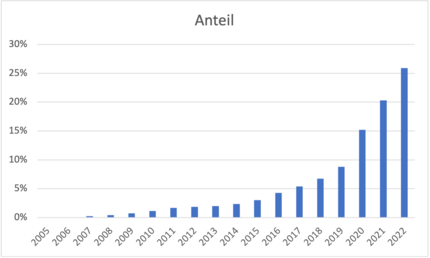

No wonder the number of new songs coming out is growing exponentially. This development isn’t just affecting music, but pretty much all digital content. Photos, videos, games – there’s been an art explosion everywhere in recent years. This graph shows the proportion of videos uploaded to YouTube between 2005 and 2022, based on a 2023 study, using 1,000 randomised samples. The trend is clear.

Attention is the currency of the 21st century. And how attention is distributed on YouTube is similar to Spotify. A minority of videos are streamed frequently, the vast majority rarely or never. According to the study, half of all YouTube videos were viewed fewer than 35 times – almost five per cent never at all. On the other hand, the most successful 0.16 per cent of videos are responsible for half of all views.

This was back in 2022, before the rise of AI slop.

The guiding principle: the winner takes it all. It’s a problem for most creators who earn a living in the content sector, the system only works for a few superstars. Everyone else earns little to nothing – even creators who can make a living from it are under great pressure to constantly crank out new hits. This in turn leads to even more overproduction.

Although there’s way more content out there, we’re not getting any different styles or unique products. Diversity has actually been falling for a long time in the charts. I wrote an article on why this is happening years ago. It has a lot has to do with the fact that commercially successful music today is optimised for streaming portals. This means, for example, that the most important feature of a song has to come in the first 30 seconds. Complex and varied songwriting? Practically impossible.

This phenomenon affects both music and the entire creative industry. Like movies. Almost every new film is a sequel, a remake or a spin-off of an ancient box office hit. Franchises are milked for all they have. Endless swaths of content are produced, but real creativity is rare.

AI is a perfect example of this. Generative AI is by definition more of the same. It creates songs, images and videos by reproducing familiar structures. It can also recombine parts of songs out of different genres – in the end, it’s still all the same style, however. Yes, there are currently more different genres in the charts than ever before. However, there have been no new musical innovations in recent years.

Experimental music and art will continue to exist in niches. But that’s exactly what we’re not hearing. People always want more of the same, and they get what they desire.

Why is it even a problem, giving the people what they want? Because: you’re not making art any more. This is fine in many cases. Music in an elevator or as background audio in a video doesn’t have to meet artistic standards. Genuine art, however, surprises, rejects conventions and expectations and thus forces audiences to engage with something new. Jazz, rock, punk, rap, techno, even pop – all these styles were scandalous in their early days and met with fierce resistance. Samba was even banned in Brazil at the beginning of the last century, musicians were persecuted and imprisoned. If people had only ever been given what they wanted, we wouldn’t have all these genres today.

Long before the AI invasion, big streaming services were only able to manage the massive amounts of content with the help of algorithms. This hasn’t really been an issue for pure music streaming portals to date, but it’s a familiar problem for Facebook and YouTube. Their algorithms that automatically block copyright infringements and other offences are very error-prone. Unjustified takedowns can put content creators in dire straits, as they’re completely at the mercy of the websites. You have to play the game according to their rules.

Mind you, detection isn’t fully automated. People still have to decide whether something should be deleted. In fact, this takes a lot of people. Only, companies don’t really want to pay them.

So, they hire subcontractors in low-wage countries such as the Philippines or Kenya (articles in German) with precarious working conditions.

The AI tsunami will only increase the need for such workers, and companies will try to keep their costs as low as possible. So the problem will only get worse. Just training AI is already digital dirty work. In machine learning, humans have to give feedback on whether recognition was good or not. Specialised companies like Outlier hire workers over the world – under astonishingly poor conditions (article in German).

How can these problems be solved? I certainly don’t know. Sure, platforms could introduce additional hurdles to limit this flood of content. However, it’s unlikely that this’ll only filter out unwanted AI material and not organic, human music. If only because there’s also mixes of the two. And excluding real human art is dangerous. Platforms would betray their ideals and promises: no more access for all, only gatekeepers as before. The American Dream, in which anyone can make it on their own, would thus be officially buried.

But even if it all works out, what would platforms gain from this? Investors need scaling. Everything has to grow, and faster than expected, in order for share prices to rise. AI makes it very easy to generate growth. It doesn’t do me any good if Spotify has 500 million new, boring songs. But that doesn't seem to matter – the big dogs on top just want to throw impressive key figures around.

AI generators such as Suno or Udio will have to answer for their actions in court in the near future. It’s more than likely these tools were trained on copyrighted material – what else? It’s quite possible that sanctions will be imposed, and that the creation of AI songs will be curbed as a result. In principle, however, their development can’t be reversed by legal means. The technology is there. Like toothpaste, it can’t be squeezed back into the tube once it's out. From my point of view, all we have left at the moment is the – probably naïve – hope that music lovers will spend their money more selectively, where it’ll directly benefit artists. Say through Bandcamp or CD purchases at concerts.

My interest in IT and writing landed me in tech journalism early on (2000). I want to know how we can use technology without being used. Outside of the office, I’m a keen musician who makes up for lacking talent with excessive enthusiasm.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all