Background information

Hands-on test of the Sony Alpha 7 V: the market leader’s back

by Samuel Buchmann

Field tests are realistic but subjective. Lab tests, on the other hand, are impartial but they often skim over the important aspects. It’s difficult to carry out either of them correctly. That’s why I’m wary of making hard and fast statements.

We don’t have a testing lab here, and that’s not about to change any time soon. So, my test will be of the everyday variety. By that I mean I’ll be trying the camera out; taking a look at the menu navigation, buttons and controls; snapping photos and jotting down my experiences. And where possible, I’ll be capturing the kind of photos the cameras are meant to be really good at according to manufacturers.

While these tests mainly focus on hands-on use, they’re inevitably subjective. I’m banking on you deeming me a competent and trustworthy tester. To bolster trust, I’ll disclose as much as possible. So, if I write that I prefer the Nikon controls to the Sony ones, I’ll follow this up with context – that I know my way around the Nikon controls better, which might account for why I find them easier to use. This should help you get a better read on my verdicts – but it’ll still be a subjective view.

My other policy is to show as much as possible rather than make empty claims. That works really well these days. For example, on modern cameras, I can capture exactly what I see in the viewfinder. This is a recording of my own viewfinder image, which is also shown on the computer 😉.

All the same, field tests are still a bit unsatisfactory. What we want are hard facts. Measurements. Image noise at ISO 100, 200, 400, 800, all the way up to 51 200 or 102 400. The dynamic range of the sensor, exact information in exposure values. The shutter lag of the autofocus, measured in milliseconds. How many photos it can take before the battery runs out. How many images per second autofocus can work its magic on. The people want facts!

But the problem is figures and data suggest the kind of precision and objectivity that’s so often not available. In this kind of fact-based test series, there’s so much that can be done wrong. And every mistake distorts the result. When I first started testing cameras in the noughties, I tried to carry out these kinds of tests but it was in a kind of amateurish way. The more I learnt about cameras, the more I realised the tests I was doing weren’t watertight. That’s why these days I tend to think I’d rather not give any specific measurements than ones that are misleading.

I wanted to measure image noise. That used to be an important criterion. Compact cameras in particular produced extremely noisy images. So, I put the camera on a tripod and photographed a sign that had text in different sizes. Then I took a photo at every ISO value and examined how the image noise increased with the ISO value. You can’t always tell the extent of the noise with the naked eye. I’d have had to have measured the images using special software. Instead, my indicator was which size of text was still readable on the sign. The reasoning behind this is that noise also takes away the definition and outlines fray.

But obviously, the sharpness of an object doesn’t just depend on the ISO value. It’s also down to the lens, the chosen aperture, to any little camera shakes that you can also get when you’re using a tripod, as well as the focus to a certain extent.

I kept discovering problems that this kind of test entails.

To make matters worse, my nice test sign was littered with a constantly growing mountain of cardboard boxes. At that time, I didn’t have a lab so I had to make the office inbox double as one. Once the boxes became impossible to move even temporarily, my series of tests was over. Looking back, I have to admit I’m glad.

I could have gotten rid of some of the problems with a better test set-up. But when you compare the camera images, one thing is certainly clear. All of the photos have to be taken in the same way. Any changes to the set-up cause problems. Agile methods and constantly optimising are things that don’t work here. Everything has to be done right from the start.

Lab test aren’t flexible. It’s difficult to set them up properly, and when you do manage it, you have to keep it that way for all the tests. But that’s not realistic for a constantly changing tech world.

Let me give you an example. In 2003, the Japanese industry association CIPA determined a testing method for battery life. To ensure a direct comparison, the test hasn’t been changed to this day. However, the test is designed for compact cameras of the time and includes elements such as extending the zoom lens and taking flash photos. Cameras that don’t have a built-in zoom lens or flash go through the test without these – which gives them a massive advantage.

Over time, aspects of a camera that are important and the areas where there are big differences also change. Image noise, for instance, is much less important these days. There doesn’t need to be much progress to get to a level where a camera meets the highest standards. Not just because the sensors create less noise, but also because high-performance image stabilisers and fast lenses with high ISO values are rarely required. Of my private collection, totaling around 32,000 photos, only 23 have an ISO value above 12,800. And I only took those to test out high ISO values. Almost half of all my photos were taken with the lowest ISO value that the camera could shoot at.

These days, it’s autofocus and video features that separate the wheat from the chaff. But I’m yet to find a lab test that can measure autofocus subject tracking.

As the overall level of digital cameras has been high for years, lab tests have mostly been for things you hardly use in daily life. That’s what makes lab tests lose their relevance. If you can only detect a difference in the laboratory, it’s insignificant in practice.

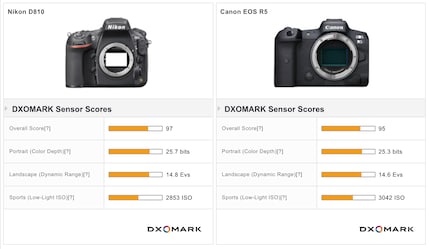

This becomes particularly clear in DxOMark lab tests. These only tested sensors; the rest of the camera didn’t even come into it. Even when it comes to the sensor, the test didn’t take into account resolution and readout speed. Given that sensors have stagnated at a high level for years as far as these test criteria are concerned, it’s certainly possible for an old camera to perform better than a new one. For example, the 2014 Nikon D810 achieves a slightly higher score than the 2020 Canon EOS R5.

But the difference is slighter than the naked eye would be able to spot. In terms of colour depth, the difference is a mere 0.4 bits. DxOMark explains that when the difference is less than 1 bit, it’s barely noticeable. And anything above 22 is excellent. Both of these cameras achieve more than 25 bits. It’s a similar story with dynamic range. Anything over 12 light levels is excellent. And in this instance, there are 14 to 15 light levels. The difference we’re talking about is 0.2 levels – anything less than 0.5 levels isn’t noticeable. With the ISO score, the difference has to be at least 25% in order to be able to see it. That’s nowhere near reality.

If your super-duper camera doesn’t perform as well in DxO as a cheap model from 2017, all I can say is relax. Everything is fine. Your camera might not be better in the areas measured, but that’s not what it’s about in 2021. Instead, be happy with your improved autofocus, the better video features, higher speed and, above all, that it’s a camera that’s better suited to you.

Sometimes I try to find the middle ground between a field and lab test. I take test photos with completely uninteresting subjects – but they’re photos designed to make a strength or weakness visible. When I photograph my carpet perpendicularly from above, for instance, it’s not your standard kind of photo. It’s not like anyone wants a picture of that. But the symmetrical structure lets me know if the lens is much more blurred at the edges than in the middle. It’s no lab test in the sense that it’s not exact, but it does give you a rough impression. And yet, even here I have to make sure I carry out the test properly. If I don’t hold the camera exactly perpendicular to the carpet, the shallow depth of field will be noticeable. The focus area should be in the corner if I want to assess the definition there.

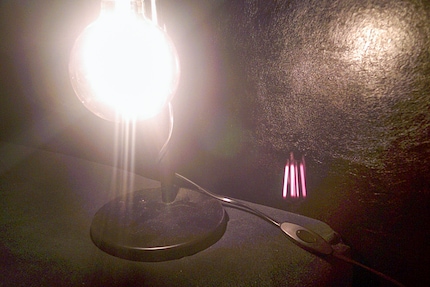

It’s even harder to find a test scenario that would make the dynamic range visible. In the past, that was apparently easier: photograph a grey gradient on paper and check how many brightness levels are lit correctly at the same time. These days, cameras are way too good for that. They capture everything correctly. There’s not a hint of over- or underexposure. To demonstrate it, I have to shoot in a light source.

But highlighting the differences between the cameras isn’t so easy. The filament is always overexposed, even with the best devices – and the rest most cameras manage effortlessly.

Even if the brightness was better graded, there’d still be a fundamental problem with photographing a light source. Namely that lens reflection lights the darkest areas so that, once again, it can’t be clearly measured.

What all of this shows is that even supposedly simple test shots are tricky. In the worst case scenario, I’d end up showcasing the weaknesses of the test rather than the weaknesses of the camera.

So, what options do we have when both field and lab tests are unsatisfactory and problematic? In my opinion, the only way forward is to be as open and frank as possible. Testers should make tests easy to understand and be very transparent. This means giving the reasoning behind test methods as well as disclosing how subjective you are, declaring any personal interests, prior knowledge, preferences and dislikes. Gone are the days when journalists could simply state: that’s the way it is because I say so, and I’m the one who’s tested it. Thankfully.

Of course, not everyone wants to wade through boring explanations or even verify things themselves. In fact, a lot of people skip straight to the verdict in reviews, as they’re not at all interested in how the tester came to that conclusion. Nevertheless, this information should be there for those who are keen to know more.

I also like to reference other sites that carry out lab tests. Or other tests beyond my scope. But only when I understand the test and think it’s reliable and important. As it happens, that would be my top tip: seek out other opinions. Just make sure to check the source and don’t be swayed by charts and diagrams you can’t even get your head around.

My interest in IT and writing landed me in tech journalism early on (2000). I want to know how we can use technology without being used. Outside of the office, I’m a keen musician who makes up for lacking talent with excessive enthusiasm.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all